The Art of Hiding

A guest essay by Elissa Altman.

The night that I saw him pour a fifth of Jim Beam into the punch bowl at my Sweet Sixteen party, I was getting ready to leave for a month at tennis camp near Boston. We were standing in our crowded Queens apartment foyer, and out of the corner of my eye, I caught my father taking the bottle out of a bag and unscrewing the cap; he winked at me like it was our secret, out of view of my grandmother who was in the kitchen sticking pink and yellow candles into my Carvel birthday cake, and my mother, who had recently divorced him and spent most of the party locked in her bedroom. On that late June night in 1979, I couldn’t taste the whiskey in the punch, and neither could my friends; grainy Polaroid photos show us milling around in our living room and acting like normal teenagers. I left for camp a few days later, too young to officially drink beyond the furtive sips of sacramental wine that my father gave me during the Jewish holidays, and at formal dinners in Manhattan restaurants, but it didn’t matter: I packed into a can of yellow Slazenger tennis balls a small stash of the Percocet I’d hoarded from the foot surgery I’d had a few weeks earlier. I never took them—I hated pills then and I still do--but I wanted options, and at sixteen, I already understood the art of hiding.

By the end of July, camp was over, and I was sent by my father to work for an upstate New York hotel for the rest of the summer until it was time to go back to school. It was owned by a friend of his and located in the gentile part of the Catskills – not the borscht belt, where bottles of cloyingly sweet Manischewitz sat unopened on every table during lunch and dinner – and the proximity of two white clapboard Methodist churches that flanked the dining room prohibited the serving of any alcoholic beverages at mealtime. The guests, many of them repeats who had been coming for decades with their families, figured out how to easily skirt the rules: they poured their vodka into Styrofoam coffee cups and their red wine into empty Welch’s grape juice bottles, and the hotel owners looked the other way. The actual hotel bar, where drinking was allowed, was on the ground floor of the dining room, and opened up to a landscaped stone patio that faced the pool where I was the lifeguard; it was here where I found my father sitting every Friday evening that August, drinking the first of three nightly gin Gibsons after he made the long drive upstate from his office in Manhattan. Newly single, he was dating a woman named Judy, who was the hotel’s front desk manager; thirty years his junior, she lived in the staff quarters down the hall from my room, which contained a tiny, sulfuric corner sink and a buggy cotton ticking single mattress perched on a Depression-era iron bed frame just big enough for me to share with a local teenager named Richard, who brought a half gallon of Almaden Mountain Rhine and a package of condoms with him whenever he came to stay with me after his nightly shift in the hotel snack bar was over.

I never want to see you hiding anything, my father said to me one Friday night at the bar, when I told him about the guests siphoning grape juice out of their Welch’s bottles in their cottages where no one could see them. If you want a taste of alcohol, come to me and ask, and I’ll teach you how to drink safely. Promise me.

I promise, I said, sipping my Genesee Cream Ale out of a tall juice glass as I sat next to him, my feet dangling off the black vinyl bar stool.

—because, he added quietly, Jews don’t drink.

I came into my father’s life late; he was thirty-nine when I was born, having already fought in World War II, having been engaged five times, having lived for a few years in Ontario before returning to America. The only son of an Orthodox cantor and a homemaker who koshered her own meat for Sabbath dinner, he grew up in a home that believed in wine strictly as sacrament, and directly connected to the commandments of the Almighty, like Moses himself. In Jewish scripture, wine represents the holiness and separateness of the Jewish people, and is used for the sanctification of the Sabbath, of Yom Tov—the six festival days in the Jewish calendar—and in animal sacrifices made in Jerusalem’s Holy Temple, the first of which was destroyed in 423 BC before being rebuilt and destroyed again by the Romans in 69 AD. Imbibed outside the confines of Jewish practice and ritual, the drinking of wine is considered a gentile endeavor and therefore inherently laced with shame, like the eating of ham or shrimp, or mixing dairy with meat; it represents worship gone off the rails, a flagrant disregard for ancient Jewish law, a form of proscribed idolatry – drinkers deify the bottle -- and a profound source of disgrace resulting in one’s excision from the Tribes of Israel, of which it is believed that all modern Jews are children.

You are a direct descendent of King David, my father would say when I was a child—so behave yourself.

My father met my gorgeous television singer mother in 1962 and they married three months later; I was born almost nine months to the day. We were an assimilated secular post-war Jewish family living in 1970s Queens, New York, doing all the things that assimilated secular post-war Jewish families did: despite Talmudic rules –- where had they gotten us thirty years earlier, when the Nazis murdered millions --- we tried to blend in with the Christians around us. My father cooked bacon and Spam to eat with our breakfast eggs. We ate cheddar on our burgers and ordered our pizza with sausage. My grandparents would never know, and my father swore me to secrecy. In the seventies, we had boozy Saturday night cocktail parties with our neighbors, and spent Sundays eating brunch in the courtyard café of the Museum of Modern Art, my mother drinking tall Bloody Marys and my father, cold Bombay Sapphire gin and tonics. We went out to every great restaurant in Manhattan; piles of The New Yorker and Cue Magazine sat stacked around the apartment. And my father came home from his job as an advertising creative director every night, kicked off his Church’s wingtips, changed out of his Brooks Brothers’ sack suit, and poured himself the first of two double Scotches.

It's my ritual he said when my maternal grandmother snidely called him a shicker – a drunk—because, as he had once told me, Jews don’t drink.

And I believed this: I believed it while my father drank his Scotch and my mother her chilled Soave Bolla on hot Queens summer afternoons with a friend and platters of Jarlsburg cheese and Triscuits. I believed it when my wealthy aunt and uncle drank tiny crystal glasses of English cream sherry at home before going out for restaurant meals, where they would have water with dinner. I believed it while sitting on a metal folding chair in a church basement forty years later, when a regular introduced herself to me after my first meeting, looked me up and down like she was searching for my horns, and said I’ve never met a Jew before.

I smiled weakly.

Of course you haven’t, I thought, ignoring the antisemitic edge to her words. Why would you.

When my parents’ marriage began to collapse under the weight of indiscretion both financial and sexual, I watched silently as my mother methodically chipped away at my father’s self-esteem, and his love of Scotch ceased being ritual and instead became idolatrous anesthesia: by the mid-seventies, he had lost his business and declared bankruptcy and could no longer care for her in the manner to which she had grown accustomed.

You’re a loser, she told him one night over our Swanson frozen turkey dinners, before getting up and leaving the table.

She took up with another man and began staying out late after finishing her job as a showroom model, leaving my father and me to sit together at our dining room table in silence, watching Let’s Make A Deal and The New Price Is Right on a tiny television, he drinking his Dewars and I, my Tab, and shame wrapped itself around us like a prayer shawl. That summer, back at the hotel in upstate New York, I began drinking nightly; no one was watching, so I didn’t have to hide. Two years later, as a freshman at college, I had a roommate who kept a bottle of Chivas in her top dresser drawer, still in its royal blue felt bag; when my father and her Presbyterian Lily Pulitzer-clad mother left after moving us in, she broke out the bottle and two small rocks glasses, and we celebrated the start of our new lives. I fell in with a group of people who were witheringly drunk on a daily basis, carrying their Long Island Ice Teas around campus in blue plastic Nalgene bottles and topping off their drinks between classes with vodka-filled bong hits. A year after that, when my grades threatened to get me expelled, I went straight and found friends who only drank on holidays, who could comfortably share a single bottle of wine between seven people, and I resorted to hiding again; I needed the possibility of insentience, of the edges being softened, of warm honey coursing through my teenage veins. Of peace, and no-pain.

After I graduated from college, I moved back home to live with my mother and her second husband. The violent chaos of her nightly emotional rages against me began to click into place as evidence of her eventual borderline diagnosis like shards of glass in a kaleidoscope. And if, at this very moment, you were to unpack the deepest shelves of her den closet, in the room where I slept for two years on a leopard-print pullout sofa before moving to my own place across town, you might find a perfectly round, balloon-shaped Tiffany wine glass covered with a thick rime of New York City dust, buried exactly where I tucked it one night in 1986 at two in the morning after slinking back into my mother’s kitchen for a quiet refill of Soave.

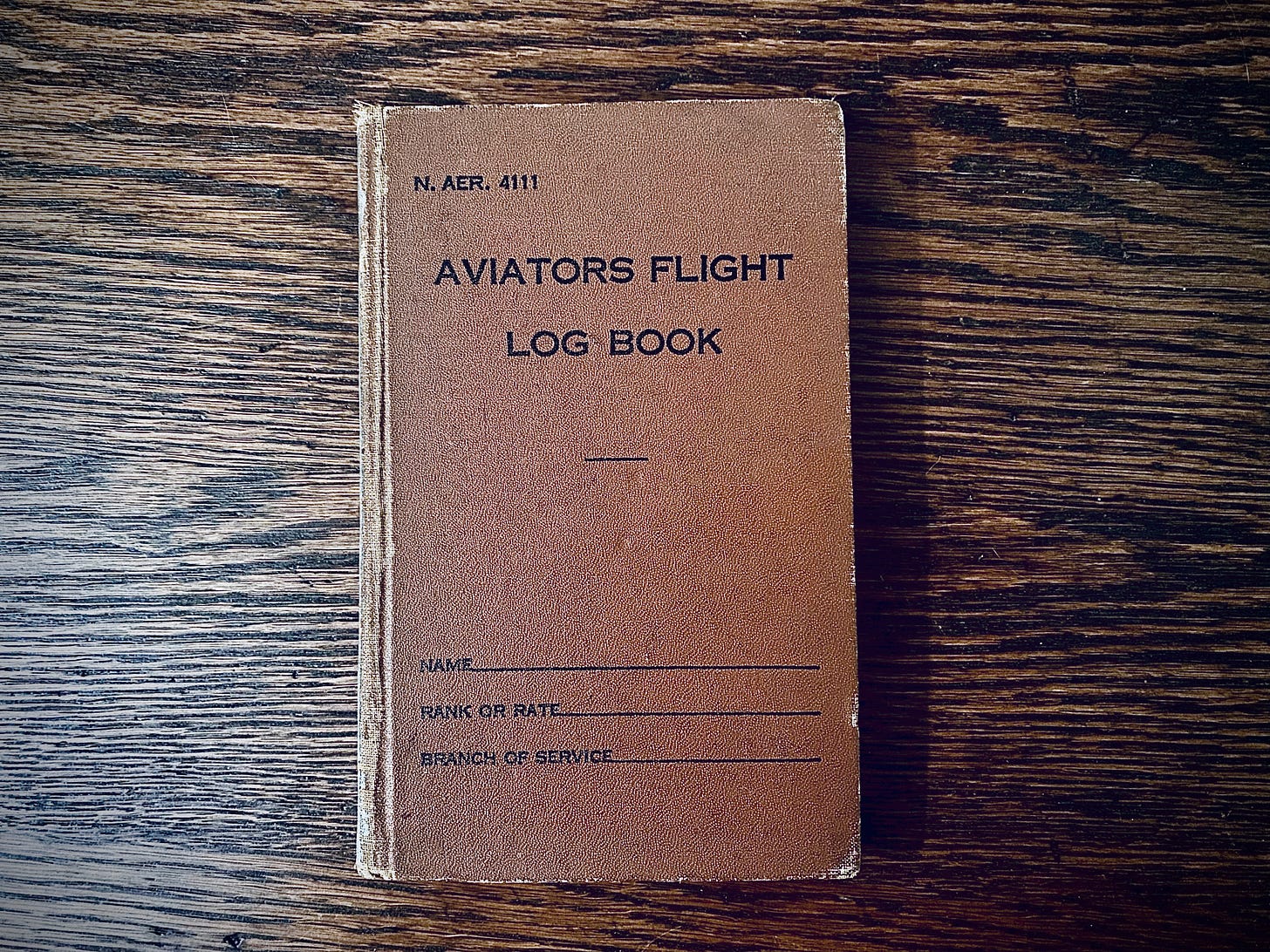

When he died in 2002, I inherited my father’s collection of 1950s jazz albums, the blue woolen Pendleton shirt I bought for his sixty-fifth birthday, his silver ID bracelet, shopping bags filled with snapshots dating back to the early thirties, and the aviator’s flight log book he was required to keep as a Naval ensign during World War II. The book documents every flight my lieutenant father piloted from October 12th 1943 to April 29th, 1945, from Texas to California to the aircraft carrier USS Enterprise in The Pacific. Each entry details the kind of plane he flew, whether he was flying solo or with a co-pilot, the length of the flight, and the weather. It was this that I was most curious about: I wanted hard evidence of a specific flight he made in 1944, during which he was inebriated and flying alone at night in a dense fog, with nothing below him but the vast ocean.

The way he first told it to me one evening at the hotel bar: he had spent hours drinking Gibsons at his officer’s club because pea soup fog had canceled every flight. But at ten o’clock that night, it lifted and—his twenty-one-year-old blood alcohol level likely stratospheric—he got the call to go.

I couldn’t walk a straight line, he said, screwing up his face like Popeye, but I took off and I made it back, looking through one eye the whole way.

My father repeated the story to me all the time, gloating at his own foolhardy bravery. A year after he dumped the Jim Beam into my sixteenth birthday punch bowl, I was drinking regularly with him like we were war buddies—sometimes beer, usually wine, brandy during the winter—and listening to his stories of youthful intoxication and the belief that nothing could possibly take him down, not even gravity, because in our world, alcohol was a sacrament, and nothing more. But when he took me to see Raiders of the Lost Ark right before I went away to college, and the Marion character, played by a tiny Karen Allen, drinks a Himalayan goon under the table while bets are placed on which one of them will pass out first, my father leaned over to me, gently put his hand on my arm and whispered, A hollow leg. Just like you.

In the fifties, there was the dude ranch he’d go to every weekend, drinking Scotch from the time he arrived on Friday until the time he left on Sunday night, driving back to the city through the throbbing haze of a blistering hangover that made him feel, he’d say, like the Russian army had just marched through his mouth. By then, my father was a Madison Avenue adman—a Madmen adman, most of whom were World War II veterans—and drinking was simply part of the assimilated clubby persona he cultivated: Gibsons at lunch with clients, Gibsons after work with colleagues, and with dates after that. I thought, for many years, that flying drunk had just been a great war story, like the one I knew about my Army captain uncle—my father’s brother in law—procuring cases of booze on the black market in France a few months after the Allied invasion, and keeping his chronically befuddled cognac-loving platoon commander drunk until VE Day by outfitting a stolen German trailer with crates of Remy and a chaise, thus saving his company from certain death at the hands of his superior.

But the story of my father flying drunk felt different; it felt like an unreachable splinter under a fingernail, a papercut accidentally dabbed with lemon juice. A shonda; a family shame of tribal proportion. There was more to it than the booze and the Talmud and the broken sacramental laws; there was the question of a death wish. My father suffered from stultifying clinical depression, as do I; going through the boxes of letters he wrote home to his parents who had once told him when he was a schoolboy earning bad grades that they didn’t want him anymore – they closed the door in his face and at nine years old, a decade before his drunken flight, he navigated the subway system by jumping the turnstile and made his way alone from Coney Island into the East Village, where his grandmother still lived in a tenement—I read his desperate yearnings for their acceptance and love.

Maybe you’ll be proud of me now, he wrote home from a Naval Air Station in Texas, when he earned his wings. I still have the letter, which my grandparents saved along with hundreds of others sent during the war.

We are so proud of you, my grandmother wrote back, but remember where you come from, and who you are.

My father’s flight logbook sits on my desk, now sandwiched between the poetry of Merwin and the essays of Wendell Berry. I never was able to track the record of his flying drunk off an unlit aircraft carrier over the black Pacific during wartime; I can only go by his word and his memory, which is all I have left of him. He died long before I began to recognize my own tendencies the way a mother notices the slant of her brow in her newborn. In my darker moments, I am still often convinced that my own journey into addiction is just a mistake, a blip, an error born of assimilation and hyperbole—it’s all impossible; Jews don’t drink—that the act of hiding it like the dusty wine glass in the den closet has become second nature to me; the inevitability of sacred disgrace is almost too hard to bear, and too biblical to metabolize. At what point does the shame of imperfection, of inadequacy, of forever being on the outside looking in overtake the simple yet elusive sense that, in a world spinning on an axis of pain, it is alcohol that allows us to soar over oceans with nothing but the stars to guide us, impervious to the laws of gravity, until we plunge to Earth.

Recently, an estranged family member wrote to me to say I hope that whatever it is you’re writing, it’s nothing that I’ll be embarrassed to have my grandchildren read as adults.

And so, the shame continues to rage like a roaring river, flowing down to the next generation and the one after that; it all continues, doesn’t it, like the stories of the Matriarchs and the Patriarchs.

Thank you,

, for this beautiful guest essay. To inquire about being featured on Love Story, please email admin@lauramckowen.com.Elissa Altman is the award-winning author of the memoirs Motherland, Poor Man's Feast, and Treyf. Her hybrid memoir on the writing life, On Permission, is coming in 2024. Her work, which has been widely anthologized, can be read in Orion, the Washington Post, On Being, Lion's Roar, LitHub, Oprah, and beyond. She teaches the craft of memoir at Fine Arts Work Center, Maine Writers and Publishers, the College of William and Mary, and internationally. Her Substack, Poor Man’s Feast, is about the intersection of sustenance, nature, and the creative spirit.

You are reading Love Story, a weekly newsletter about relationships, recovery, and writing from Laura McKowen. Laura is the founder of The Luckiest Club, an international sobriety support community, and the bestselling author of two books, We Are The Luckiest: The Surprising Magic of a Sober Life and Push Off from Here: 9 Essential Truths to Get You Through Sobriety (and Everything Else).

You can give a gift subscription here.

I wasnt planning to read your essay, Elissa, all in one go - but after starting, I couldnt stop. So beautifully written & somehow haunting but healing at the same time somehow! Thank you for your gorgeous honesty & prose.

Wow. This moved me in ways I didn’t see coming. Despite knowing what an incredible writer Elissa is, I still wasn’t prepared.

My drinking was always wrapped up and delivered to me in a package my dad dropped at my feet. I, too, was prided for having a hollow leg. I was a boastful drinker. I could throw them back with my dad. And I did. But it wasn’t until I lost my dad in 2020 that the real hiding began. My grieving brought my drinking to a new level, one that required more hiding - from myself, from my past, from my feelings. Then came inescapable shame. Shame that eventually got me sober one year later. My dad never got to witness me walking on these sober legs. Yet, he was pivotal in getting me sober. I thank him and I thank you both (Laura & Elissa) for making these words available to so many. So many who also hide and feel shame. Collectively, we can drop it.

🙏🏼💕